This free textbook is an introduction to intellectual property law, the set of private legal rights that allows individuals and corporations to control intangible creations and marks—from logos to novels to drug formulæ—and the exceptions and limitations that define those rights. It focuses on the four forms of US federal intellectual property—trademark, copyright, patent and trade secrecy—but many of the ideas discussed here apply far beyond those legal areas and far beyond the law of the United States. The book is intended to be a textbook for the basic Intellectual Property class, but because it is an open, Creative Commons licensed coursebook, which can be freely edited, copied and shared, it is also suitable for undergraduate classes, or for a business, library studies, communications or other graduate school class. The license means that teachers can take only the chapters or excerpts they need, which can be downloaded individually, and do so at no cost. Our goal is to make the book available without regard to students’ ability to pay: the free digital download can be found here. If a tangible copy is preferred, an 8”x10” paperback version is available for $35. We hope, though, that the flexibility of the digital downloads—of both individual chapters and the entire book—will be attractive. One of the goals of the Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain is to offer high quality academic research about intellectual property to the citizens of the world, in accessible formats, at no cost.

Each chapter contains a clear introduction to the field, cases and secondary readings illustrating the structure and conflicts in the theory and doctrine of intellectual property, followed by questions to test the student’s understanding. Chapters are built around a set of problems or role-playing exercises involving the material. The problems range from a video of the Napster oral argument, with students asked to take the place of the lawyers, to exercises counseling clients about how search engines and trademarks interact, to discussions of the First Amendment’s application to Digital Rights Management or the Supreme Court’s rulings on gene patents. There is extensive discussion of the theory, history and political economy of intellectual property law. This is a subject that excites widespread and passionate differences of opinion which—at least so far—do not track conventional political leanings at all. That makes it unique and, for us, uniquely fascinating as an academic endeavor. It is also something—like the environment or civil rights—that everyone might want to learn about, whether or not they are lawyers.

This edition is current as of July 15, 2021. It includes Google v. Oracle, the recent Supreme Court decision on fair use in the context of software development, and a discussion of the CASE Act. There are also notes on recent decisions in each doctrinal area and a new series of teaching aids—flow charts and checklists which help guide the student through the material and explain the process of analysis. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, this edition was written during the pandemic. We added a preface explaining how the last year showed the human importance—but also the intellectual fascination—of the questions this course covers.

About the authorsJames Boyle is William Neal Reynolds Professor of Law at Duke Law School and the former Chairman of the Board of Creative Commons. His other books include The Public Domain: Enclosing the Commons of the Mind, Shamans, Software and Spleens: Law and the Construction of the Information Society, countless widely-cited and sparingly-read law review articles, and two educational graphic novels (with Jennifer Jenkins): Bound By Law? and Theft!: A History of Music. He recently edited The Past and Future of the Internet: A Symposium for John Perry Barlow and co-authored Mark of the Devil: The University as Brand Bully, an empirical study of whether the university most often accused of being a brand-bully actually is one. Unfortunately, the answer is “yes,” and the name of the university is “Duke.”

Jennifer Jenkins is Clinical Professor of Law (Teaching) at Duke Law School and the Director of the Center for the Study of the Public Domain. Her articles include In Ambiguous Battle: The Promise (and Pathos) of Public Domain Day and Last Sale? Libraries’ Rights in the Digital Age. She is the co-author, with James Boyle, of Bound By Law?, Theft!: A History of Music, and Mark of the Devil: The University as Brand Bully.

Statutory Supplement: The Center has also published an accompanying statutory supplement that collects the primary sources of US Federal intellectual property law—Copyright, Trademark, Patent and Trade Secret—and selected treaties. This edition adds provisions from the Music Modernization Act and Marrakesh Treaty Implementation Act to the Copyright Act, and amends the Lanham Act to reflect two recent Supreme Court decisions. It is available as a free download or low cost print purchase. Even if one chooses a different casebook, simply by choosing this supplement, one can lower students’ costs substantially.

Monday, July 19th, 2021 Creative Commons, Excerpts from our forthcoming Open CoursebookIntroduction In June of 2022 a man called Blake Lemoine told reporters at The Washington Post that he thought the computer system he worked with was sentient. [i] By itself, that does not seem strange. The Post is one of the United States’ finest newspapers and its reporters are used to hearing from people who think that the CIA is attempting to read their brainwaves or that prominent politicians are running a child sex trafficking ring from the basement of a pizzeria. [ii] (It is worth noting that the pizzeria had no basement.) But Mr. Lemoine was different; For one thing, he was not some random person off the street. He was a Google engineer. Google has since fired him. For another thing, the “computer system” wasn’t an apparently malevolent Excel program, or Apple’s Siri giving replies that sounded prescient. It was LaMDA, Google’s Language Model for Dialogue Applications [iii] —that is, an enormously sophisticated chatbot. Imagine a software system that vacuums up billions of pieces of text from the internet and uses them to predict what the next sentence in a paragraph or the answer to a question would be.

James Boyle My new book, The Line: AI and the Future of Personhood, will be published by MIT Press in 2024 under a Creative Commons License and MIT is allowing me to post preprint excerpts. The book is a labor of (mainly) love — together with the familiar accompanying authorial side-dishes: excited discovery, frustration, writing block, self-loathing, epiphany, and massive societal change that means you have to rewrite everything. So just the usual stuff. It is not a run-of-the-mill academic discussion, though. For one thing, I hope it is readable. It might even occasionally make you laugh. For another, I will spend as much time on art and constitutional law as I do on ethics, treat movies and books and the heated debates about corporate personality as seriously as I do the abstract philosophy of personhood. These are the cultural materials with which we will build our new conceptions of personhood, elaborate our fears and our empathy, stress our commonalities and our differences. To download the first two chapters, click here.

James Boyle, Oct 25th, 2021

There are a few useful phrases that allow one instantly to classify a statement. For example, if any piece of popular health advice contains the word “toxins,” you can probably disregard it. Other than, “avoid ingesting them.” Another such heuristic is that if someone tells you “I just read something about §230..” the smart bet is to respond, “you were probably misinformed.”

Jennifer Jenkins and I have just published the 2021 edition of our free, Creative Commons licensed, Intellectual Property textbook.

I will probably never be published in a law review ever again after writing this. I find myself curiously untroubled by the thought.

I teach at Duke University, an institution I love. The reverse may not be true however, at least after my most recent paper (with Jennifer Jenkins) — Mark of the Devil: The University as Brand Bully. (forthcoming in the Fordham Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law Journal). The paper is about the university most frequently accused of being a “trademark bully” — an entity that makes assertions and threats far beyond what trademark law actually allows, something that is all too common, with costs to both competition and free speech. Unfortunately, that university is our own — Duke.

The Economist was kind enough to ask me to write an article commemorating the 50th anniversary of Garrett Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons. ““THE ONLY way we can preserve and nurture other and more precious freedoms is by relinquishing the freedom to breed.” This ominous sentence comes not from China’s one-child policy but from one of the 20th century’s most influential—and misunderstood—essays in economics. “The tragedy of the commons”, by Garrett Hardin, marks its 50th anniversary on December 13th.” Read the rest here.

I am posting here a draft of a chapter for Ruth Okediji’s forthcoming book on the possibilities of international intellectual property reform. In my case, the article recounts the lessons I learned from being part of the Hargreaves Review of Intellectual Property in the UK. “In the five months we have had to compile the Review, we have sought never to lose sight of David Cameron’s “exam question”. Could it be true that laws designed more than three centuries ago with the express purpose of creating economic incentives for innovation by protecting creators’ rights are today obstructing innovation and economic growth? The short answer is: yes. We have found that the UK’s intellectual property framework, especially with regard to copyright, is falling behind what is needed. Copyright, once the exclusive concern of authors and their publishers, is today preventing medical researchers studying data and text in pursuit of new treatments. Copying has become basic to numerous industrial processes, as well as to a burgeoning service economy based upon the internet. The UK cannot afford to let a legal framework designed around artists impede vigorous participation in these emerging business sectors.” Ian Hargreaves, Foreword: Hargreaves Review (2011) Read the chapter.

Ever been utterly frustrated, made furious, by an Apple upgrade that made things worse? This post is for you. (With apologies to Randall Munroe.)

Duke’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain is announcing the publication of Intellectual Property: Law & the Information Society—Cases and Materials by James Boyle and Jennifer Jenkins. This book, the first in a series of Duke Open Coursebooks, is available for free download under a Creative Commons license. If you do not want to use the entire casebook you can view and download the individual chapters (in a variety of formats) here. It can also be purchased in a glossy paperback print edition for $29.99, $130 cheaper than other intellectual property casebooks.

We are posting excerpts from our new coursebook Intellectual Property: Law and the Information Society which will be published in two weeks is out now! It will be is of course freely downloadable, and sold in paper for about $135 less than other casebooks. (And yes, it will include discussions of whether one should ever use the term “intellectual property.” ) The book is full of practice examples.. This is one from Chapter One, on the theories behind intellectual property: “What if you came up with the idea of Fantasy Football?” No legal knowledge necessary. Why don’t you test your argumentative abilities…?

Today, we are proud to announce the publication of our 2014 Intellectual Property Statutory Supplement as a freely downloadable Open Course Book. It offers the full text of the Federal Trademark, Copyright and Patent statutes (including edits detailing the changes made by the America Invents Act.) It also has a number of important international treaties and a chart which compares the various types of Federal intellectual property rights — their constitutional basis, subject matter, length, exceptions and so on.You can see it here in print, or download it for free, here.

This is the fourth in a series of postings of material drawn from our forthcoming, Creative Commons licensed, open coursebook on Intellectual Property. It is about lawyers and language.

Macaulay’s 1841 speech to the House of Commons on copyright law is often cited and not much read. In fact, the phrase “cite unseen” gains a new meaning. That is a shame, because it is masterful. (And funny.) One fascinating moment? When Macaulay warns that copyright maximalism will lead to a future of rampant illegality, as all happily violate a law that is presumed to have lost all moral legitimacy.

At present the holder of copyright has the public feeling on his side. Those who invade copyright are regarded as knaves who take the bread out of the mouths of deserving men. Everybody is well pleased to see them restrained by the law, and compelled to refund their ill-gotten gains. No tradesman of good repute will have anything to do with such disgraceful transactions. Pass this law: and that feeling is at an end. Men very different from the present race of piratical booksellers will soon infringe this intolerable monopoly. Great masses of capital will be constantly employed in the violation of the law. Every art will be employed to evade legal pursuit; and the whole nation will be in the plot… Remember too that, when once it ceases to be considered as wrong and discreditable to invade literary property, no person can say where the invasion will stop. The public seldom makes nice distinctions. The wholesome copyright which now exists will share in the disgrace and danger of the new copyright which you are about to create.

The legal change he thought would do that? Extending copyright to the absurd length of life plus 50 years. (It is now life plus 70). Ah, Thomas, if only you could have been there for the Sonny Bono Term Extension debates.

This is the second in a series of postings of material drawn from our forthcoming, Creative Commons licensed, open coursebook on Intellectual Property. The first was Victor Hugo: Guardian of the Public Domain The book will be released in late August. In 1906, Samuel Clemens (who we remember better by his pen name Mark Twain) addressed Congress on the reform of the Copyright Act. Delicious.

Jennifer Jenkins and I are frantically working to put together a new open casebook on Intellectual Property Law. (It will be available, in beta version, this Fall under a CC license, and freely downloadable in multiple formats of course. Plus it should sell in paper form for about $130 less than the competing casebooks. The accompanying statutory supplement will be 1/5 the price of most statutory supplements — also freely downloadable.) More about that later. While assembling the materials for a casebook, one gets to revisit the archives, reread the great writers. Today I was revisiting Victor Hugo. Hugo was a fabulous — inspiring, passionate — proponent of the rights of authors, and the connection of those rights to free expression and free ideas.

Today is the second day of “Copyright Week!” Talk about a lede. That sentence has all the inherent excitement of “Periodontal Health Awareness Week” or “‘Hug Your Proctologist! No, After He’s Washed His Hands’ Week.” And that’s a shame. Copyright Week is a week devoted to our relationship with our own culture. Hint: things aren’t going well. The relationship is on the rocks.

Professor Alex Sayf Cummings, author of a fascinating book called Democracy of Sound: Music Piracy and the Remaking of American Copyright in the 20th Century (recommended as a thought-provoking read) has an interesting post up about attempts to shut down music lyric sites such as Rapgenius.com.

Academics (and others) arrange conferences. Perfectly normal people are invited to those conferences to speak. Most of them are just as charming as can be… but then there are the special ones. This Top 10 List of the special people one has to respond to is devoted to all conference planners everywhere. Hold your heads up high. After this, purgatory should be a snap.

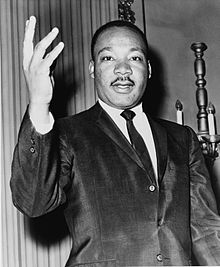

August 28th, 2013 is the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. The copyright in the speech is administered by EMI, with the consent of the King family. Thus the speech may not be freely played on video or reproduced and costlessly distributed across the nation — even today. Its transient appearance depends on the copyright owner’s momentary sufferance, not public right. It may disappear from your video library tomorrow. It has even been licensed to advertise commercial products, including cars and mobile phone plans.

Aaron Swartz committed suicide last week. He was 26, a genius and my friend. Not a really good friend, but someone I had worked with off and on for 11 years, liked a lot, had laughed with frequently, occasionally shaken my head over and deeply admired.

An Intellectual Property System for the Internet Age James Boyle In November 2010, the Prime Minister commissioned a review of the Britain’s intellectual property laws and their effect on economic growth, quoting the founders of Google that “they could never have started their company in Britain” because of a lack of flexibility in British copyright.. Mr. Cameron wanted to see if we could have UK intellectual property laws “fit for the Internet age.” Today the Review will be published. Its conclusion? “Could it be true that laws designed more than three centuries ago with the express purpose of creating economic incentives for innovation by protecting creators’ rights are today obstructing innovation and economic growth? The short answer is: yes.” Those words are from Professor Ian Hargreaves, head of the Review. (Full disclosure: I was on the Review’s panel of expert advisors.)

A slideshow and downloadable book remembering Keith in words and pictures. You can order a glossy, high quality copy of the book itself here from Createspace or here from Amazon. We tried to make it as beautiful as something Keith would create. We failed. But we came close; have a look at how striking it is… all because of Keith’s art.