Over the last year the music industry has been in flux as artists, labels, and streaming services jockey over the best way to build the future of their business. Taylor Swift pulled her catalog from Spotify; Tidal launched a new platform owned by artists, not record companies; and Apple is preparing to muscle in on the market with its own offering. The one thing missing from much of this discussion has been the details on how deals get done between these groups, but that is no longer the case.

The Verge has obtained a contract between Sony Music Entertainment and Spotify giving the streaming service a license to utilize Sony Music’s catalog. The 42-page contract was signed in January 2011, a few months before Spotify launched in the US. Written by Sony Music, the two-year deal — with an optional third year that Sony Music could pick up — reveals how much Spotify must pay in yearly advances to Sony, the subscriber goals that Spotify must hit, and how streaming rates are calculated. contracts like these have been kept secret, until now

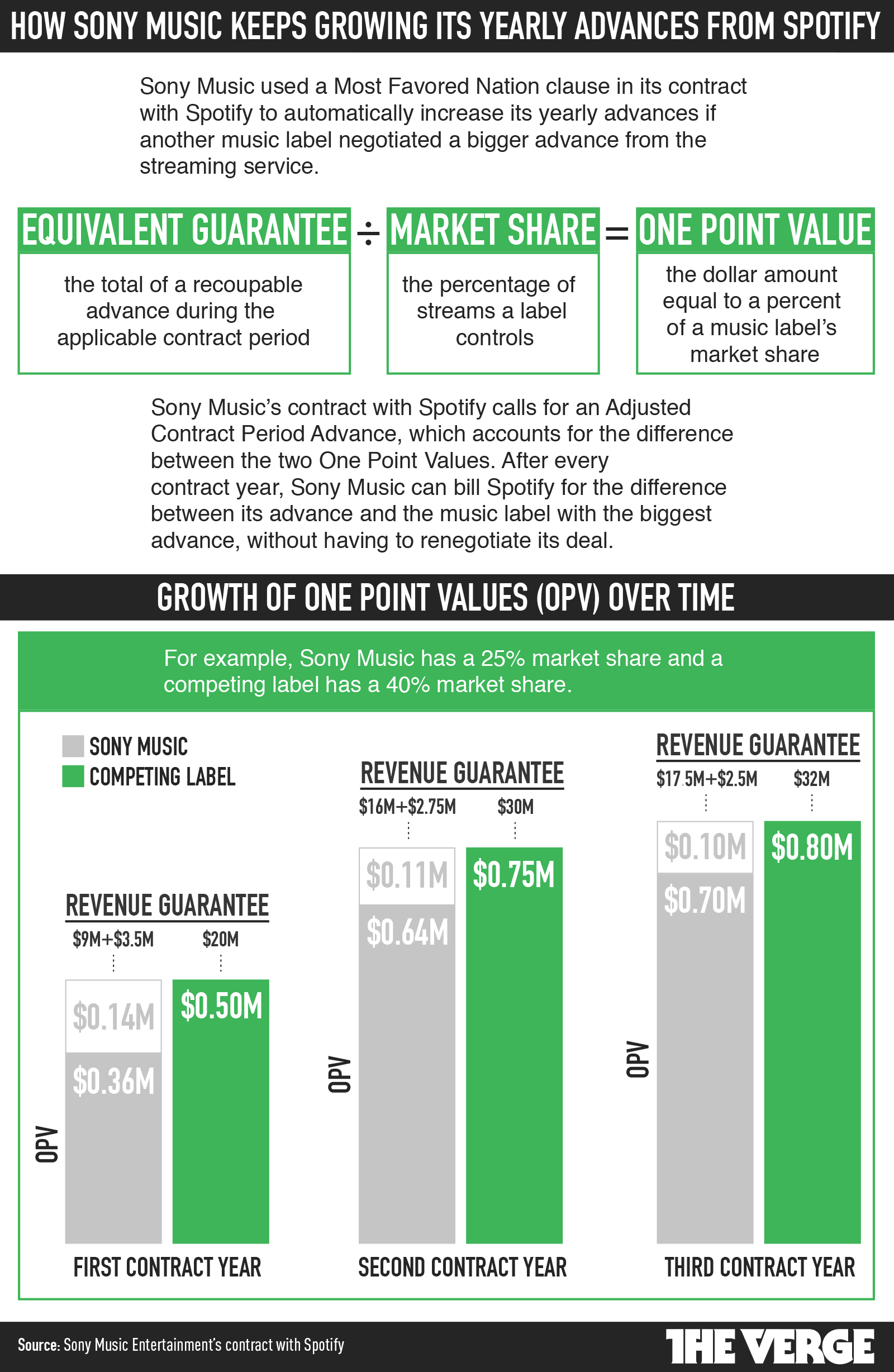

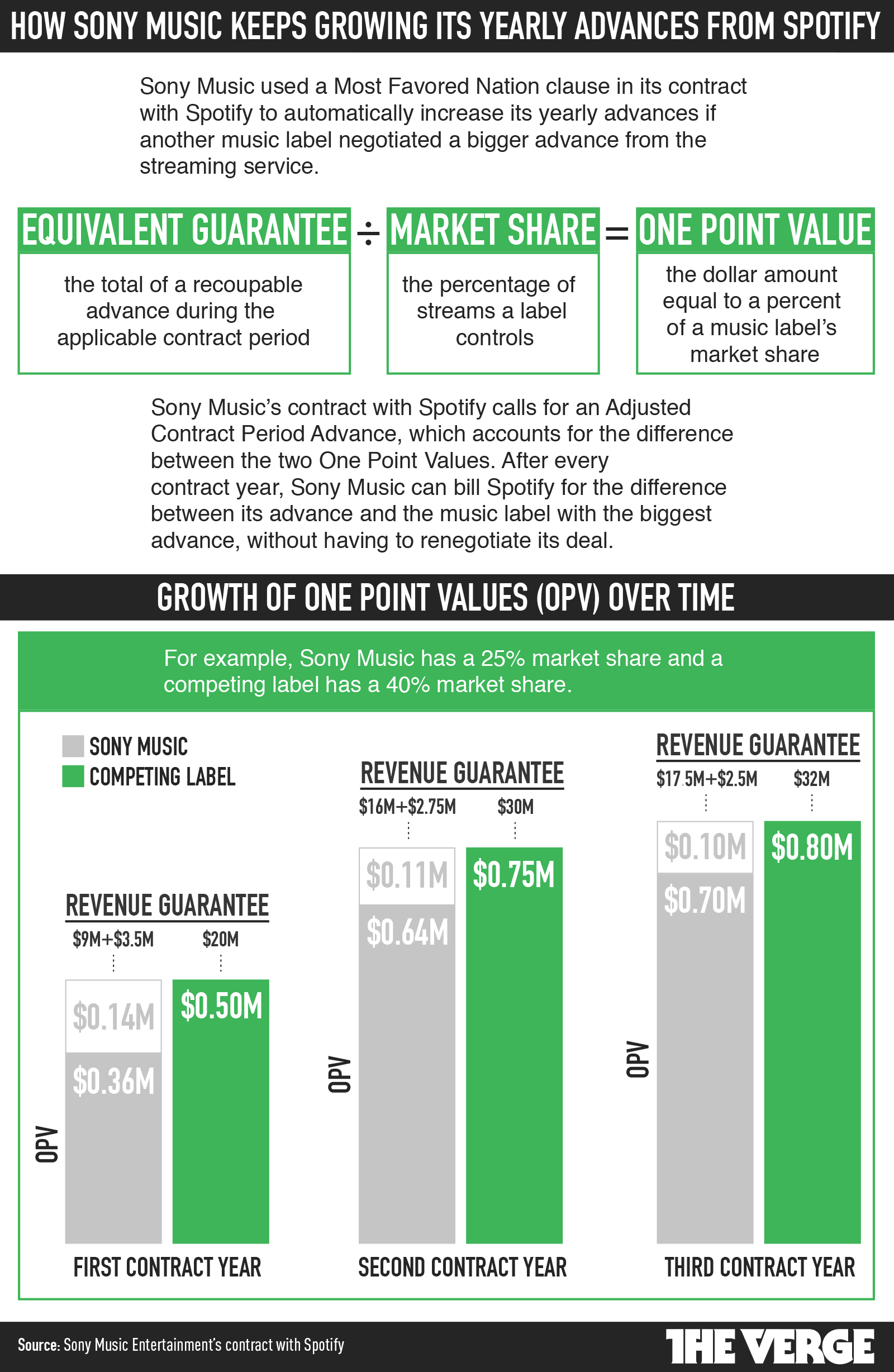

More interestingly, the contract details how Sony Music uses a Most Favored Nation clause to keep its yearly advances from falling behind those of other music labels, how Spotify can keep up to 15 percent of revenues "off the top" from ad sales made by third parties, and the complex formula that determines how much labels get paid per stream.

This contract — like every other contract involving a music label and a streaming service — has been secret until now. Given the myriad ways Sony Music came out as the winner, it’s worth asking who really should shoulder the blame for the lackluster streaming payments that artists like Swift have been complaining about — the labels or the streaming service?

At the request of the copyright owner, the contract has been removed.

In section 4(a), Spotify agrees to pay a $25 million advance for the two years of the contract: $9 million the first year and $16 million the second, with a $17.5 million advance for the optional third year to Sony Music. The contract stipulates that the advance must be paid in installments every three months, but Spotify can recoup this money if it earns over that amount in the corresponding contract year.

But what the contract doesn’t stipulate is what Sony Music can and will do with the advance money. Does it go into a pot to be divided between Sony Music’s artists, or does the label keep it to itself? According to a music industry source, labels routinely keep advances for themselves.

According to a music industry source, labels routinely keep advances for themselves

"I’ve worked at the major labels, and I’ve worked at the indies, so I’ve seen both sides of the business," says Rich Bengloff, president of the American Association of Independent Music. "A lot of the time, money that is paid outside of the direct usage doesn’t end up getting shared."

Sony Music’s Most Favored Nation clause is the most intriguing piece of its contract with Spotify. Section 13 essentially makes every major aspect of the contract amendable if any other label has a better deal or interpretation of that aspect than Sony Music. Section 13(2) lists the provisions which can be amended in Sony Music’s contract if a better deal is obtained by another music label, including what constitutes an "active user," the definition of gross revenue, and any improved security provisions. Sony Music can call on an independent auditor once a year to determine whether Spotify has struck a more agreeable deal with any other labels.

Having an MFN clause in a contract is standard for music licensing contracts, according to multiple sources. MFNs have garnered scrutiny in the past, and as part of its merger with EMI in 2012, Universal Music Group had to stop using the clauses in Europe for 10 years . But they remain legal in the US.

Where the MFN clause truly comes in handy for Sony Music is when it’s used in conjunction with section 5, the "annual true-up of advances" clause. This clause makes sure Sony Music’s yearly advances from Spotify are on par with the best deal negotiated by any other label based on the percentage of market share. That means if another music label is getting paid $1 million by Spotify for each percentage of market share it has, and Sony Music is getting $600,000 per market share percentage, Spotify must pay Sony Music the $400,000 difference — known as the adjusted contract period advance — at the end of each contract year.

One of the murkiest clauses in the contract is hidden under the contractual definition of gross revenues in section 1(vi)(bb). The clause states that gross revenue includes "actual out-of-pocket costs paid to unaffiliated third parties for ad sales commissions (subject to a maximum overall deduction of 15 percent "off the top" of such advertising revenues)." In English, that means that Spotify can keep up to 15 percent of all advertising revenues generated by the ad sales that are handled by third parties hired by the streaming service.

How much money that amounts to depends on a number of factors, including what percentage of Spotify’s ads are sold by third parties, and if it chooses to keep the full 15 percent to itself. Spotify may also use these funds to recoup the commissions it has to pay to the third-party companies it uses to sell its ads.

Spotify has tried to counter criticisms about what it pays artists

But regardless of the amount, it’s money that is not accounted for in Spotify’s gross revenue total, which is split 70/30, with 70 percent going to the labels and publishers and 30 percent to Spotify. Spotify pulled in €98.8 million ($110M) in advertising revenue in 2014. The company has gone to great pains to map out for the public exactly what it pays, in part as a public relations move to try and counter criticisms about what it pays artists. But in that detailed explanation, it never mentions this 15 percent.

In addition to the advance Spotify must pay Sony Music, it is also required to give the music label free ad space on its service. The "credit for advertising inventory" clause mentioned in section 14(a) grants Sony Music a total of $9 million in ad space ($2.5 million in the first year, and $3 million and $3.5 million in the subsequent years). And the free ads don’t come at market rates either — they must be given to Sony Music at a heavily discounted rate.

Sony Music could in effect sell the free ads it has been given for millions

While it's possible Sony Music could use that ad space to promote its own artists, section 14(e) gives the label "the right to resell the credited inventory at prices determined by the label in [the] label’s sole discretion." Section 14(a) also requires Spotify to make an additional $15 million of ads at a discounted rate available for purchase by Sony Music. Sony Music could in effect sell the free ads it has been given for millions, and turn around to buy more ads at a reduced price. But that’s not all — in section 14(p), the contract states Spotify must offer a portion of its available unsold ad inventory to Sony Music for free to allow the label to promote its own artists.

Of course, the biggest question is how much Sony Music gets paid per stream, and well, it’s complicated. Section 10 shows how Sony Music separated its label fees into three distinct tiers — the ad-supported free tier, online day passes (which no longer exist), and Spotify’s premium service. In each of those segments, Sony Music can pull in a revenue share fee that is equal to 60 percent of Spotify’s monthly gross revenue multiplied by Sony Music’s percentage of overall streams. (So if Spotify earned $100 million in gross revenue, the labels would would get $60 million. If Sony Music made up 20 percent of the streams, it would take home $12 million.)

But there is another far more complex formula that can earn Sony Music even more money from Spotify. The contract has what’s known as the usage-based minimum and per subscriber minimum, covering the free and paid tiers, respectively. If the royalties from usage in any particular month are greater than what is paid out by the revenue share, Sony Music gets that amount instead.

Under the usage-based minimum for the free tier, section 10(a)(1)(ii) stipulates Spotify must pay $0.00225 per stream, thanks to a discount that lasts for the length of the contract. If Spotify somehow missed its growth targets in the preceding month, that number could jump to $0.0025 per stream. These rates only come into play if the usage-based minimum exceeds the revenue sharing model.

Streaming payouts are subject to a very complex formula

The premium tier’s per subscriber minimum takes Sony Music’s label usage percentage and multiplies it by the number of premium subscribers on Spotify, multiplied by $6.00. Once again, this model is used only if the total payout exceeds the revenue share.

While the amount Spotify doles out is often discussed in terms of payment per stream, the contract shows just how complex and variable that payment can be. It’s likely that some months the usage or per subscriber minimum could generate a bigger payout for Sony Music than the revenue share does, especially with a popular new release.

Spotify has argued that while "it is possible to reverse engineer an effective ‘per stream’ average by dividing one’s royalties by the number of plays that generated them. this is not how we measure our payouts internally nor is it a reliable yardstick for Spotify’s value to artists." This contract shows why.

Even with this contract, it’s still difficult to tell how much artists are getting paid by Spotify.

Sony Music is likely getting considerable payouts from Spotify each year, but what it does when it gets that money — and how much of those payments actually make it down to the artists — is still unknown. Some artists have clauses in their contracts to get a larger share of the streaming revenue, and some artists are still operating under CD-era contracts that only give them 15–20 percent of their streaming revenues.

"You can’t squeeze blood from a stone."

Spotify has been renegotiating its licensing contract with some music labels, according to sources, and how those deals will shake out is still undetermined. But given the economics of Spotify’s first deal with Sony Music, it’s likely that Sony Music and other labels will ask for an even larger advance from the streaming service.

In the wake of Swift’s departure from Spotify, many musicians rallied to her cause, vilifying streaming services that paid a fraction of a penny per play. But this contract makes it clear — the pay per stream rates aren’t the only issue. According to its financial disclosures, the majority of Spotify’s revenue, around 80 percent, has been flowing out the door to the rights holders. "You can’t squeeze blood from a stone," said David Pakman, the former CEO of eMusic and partner at Venrock. "Your beef can’t be with Spotify anymore." At least not with Spotify alone.

Sony Music and Spotify declined to comment.

Additional reporting by Ben Popper